Binding to Python

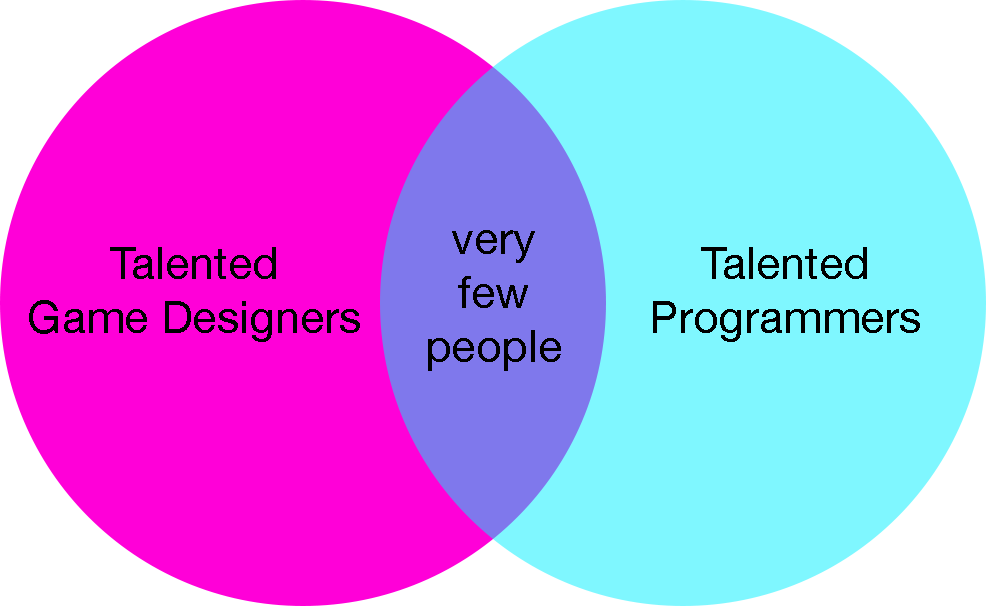

Not everyone who makes games has a degree in Computer Science like me. Likewise, I’m not going to pretend to be a wiz at level design. There’s no shortage of creative individuals who want to make games but lack the programming skills to develop natively in C++. And you can’t blame them. C++ is a scary language with countless esoteric nuances that create a high barrier to entry.

Furthermore, C++ often isn’t the best tool for the job. If you’re trying to design a level and want to make sure you’ve got this box in juuuuust the right place so that the player is given a challenge to jump up onto it, it would be frustrating to keep changing a float in C++ and wait for the entire project to recompile after every slight adjustment.

User-facing features subject to frequent change and don’t require optimization typically don’t belong in C++. Instead, we have a higher level scripting languages which invoke the low-level code the engine is natively built in.

In Unreal we have a node-based scripting language called Blueprints. In Godot there’s also a node-based scripting language, but also bindings to other languages such as C# and Rust.

Why Python?

In my engine, I picked Python as my high-level scripting language. The reasoning behind this was arbitrary. I could have bound C++ to any other language and in fact there’s no reason I can’t support multiple other languages. I simply picked Python because:

- I already knew it.

- I knew binding to C was commonly done and I would find plenty of documentation on how to do it.

- I didn’t have the time to develop my own language, particularly a node-based visual scripting language.

A common contender to Python you see in game development is Lua, which is an impressively lightweight scripting language. I believe Lua is popular in game development for 2 reasons:

- Binding to C is simple (significantly more so than Python).

- It can double as a configuration language, replacing JSON or XML as your serialization format.

However I went with Python of Lua for two main reasons:

- I already knew Python and I’d rather not learn a new language on top of creating bindings.

- Python has many more 3rd party libraries.

So with my mind made up on using Python, I started researching what libraries were out there that could help me.

Binding Libraries

Binding C++ to Python is not a new or novel task in any way. In fact, most Python libraries are implemented natively in C/C++ for performance. So there’s no shortage for first and third party libraries for creating these bindings. Here’s the ones I looked into:

pybind11boost::pythoncppyy- The Python Foundation’s official C API

I spent many hours trying all of these out. pybind11, boost::python, and cppyy all shared one fatal flaw though: lack of C++20 support. This was a complete deal breaker for me since the primary goal of my engine is an intense focus on C++20 features.

That said what I saw from these three higher level binding libraries was very impressive. pybind11 and boost::python had very simple and easy ways of creating bindings on the C/C++ side. However, I’m apprehensive about including boost as a dependency to my engine since that is an immense library to depend on when I only need one small part of it. If this were a larger project, perhaps a more fully-featured engine, I would have no problems including boost since I’m sure I could find plenty of places to use its powerful utilities.

cppyy was an extremely impressive tool. I believe this might be the future of C/C++ bindings to Python. It exists entirely on the Python side without having to modify your C/C++ code at all. Perfect for if you only have headers and binaries with no original source code. It works by using its own JIT compiler to create the necessary debug symbols to the code. The compiler it uses is cling, which is CERN’s fork of clang. Unfortunately like pybind11 and boost::python, it also didn’t support C++20 and there is little I could do to change that short of contributing to the open source project directly.

This left me with only one option: The Python Foundation’s official C API. This is a very intimidating library on first approach, especially knowing that so many other developers found it so cumbersome that there’s at least three different wrappers to it. It was also extremely awkward since this API is C99 compliant while my engine is C++20. So here I am now trying to bridge the gap to a subset language from 21 years in the past.

Using the Python C API

Defining a custom class with the Python C API follows this pattern:

#include <Python.h>

typedef struct

{

// basically saying that we inherit from Object

PyObject_HEAD

// put other data members here as you normally would

int someData;

} PyMyClass;

// array of all instance variables

static PyMemberDef PyMyClass_members[]

{

{

// the syntactical name for this variable in Python

"someData",

// flag declaring its type

T_INT,

offsetof(PyMyClass, someData), 0,

"documentation about the purpose of this variable"

},

// sentinel declaring the end of this array

{ NULL }

}

/**

* @param self reference to `this`

* @param args tuple containing all the arguments passed

* @param kwds optional tuple of all the strings used in this invocation

*

* @returns reference-counted pointer to some python object

*/

PyObject* PyMyClass_DoSomething(PyObject* self, PyObject* args, PyObject* kwds)

{

// manually handle all possible overloads by parsing `args` and `kwds`

// also a good idea to check that `self` actually references a `PyMyObject*`

// always return a `PyObject` here, never NULL

}

// array of all methods this class has

static PyMethodDef PyMyClass_methods[]

{

{

// the syntactical name for this method in Python

"DoSomething",

(PyCFunction)PyMyClass_DoSomething,

// flag whether this method takes no args, some args, variadic args, keywords, etc.

METH_NOARGS,

"documentation about what this function does"

},

// sentinel declaring the end of this array

{ NULL }

}

// All the type information for this class.

// Think like type_info in C++.

static PyTypeObject PyMyClass_type

{

// again, saying that we inherit from Object

.ob_base = { PyObject_HEAD_INIT(NULL) 0 },

// the syntactical name for this class in Python

.tp_name = "MyClass",

.tp_members = PyMyClass_members,

.tp_methods = PyMyClass_methods

}

As you can see, this is a very C-oriented way of doing things. Indeed, this is a good way of implementing polymorphism in C. However, I’m in C++, not C, so there’s some improvements to the standard convention I can make.

There’s some obvious C-isms we can replace with C++isms. Such as replacing NULL with nullptr, C-style casts with the various C++ casts, avoiding the use of typedef, etc.

You’ll also notice that we prepend all variables such as PyMyClass_methods with the name of the class they belong to. This makes sense in C where we have no namespace resolution. However in C++ I would rather use syntax such as py::MyClass::methods.

Also notice that the PyObject_HEAD macro simply expands to defining a PyObject as a data member. This is the exact same memory layout as if we’d just C++ inherited from PyObject. So that’s what we’ll do instead.

All methods take the self pointer as the first argument. This is something we can exploit. If you consider how methods are implemented in C++, they’re all really free-functions which have the this pointer as the first argument. Indeed, that’s how they’re invoked. So all of these free functions such as MyPyClass_DoSomething can become actual methods and we can trust the compiler to put the self pointer onto the call stack exactly where the this pointer is expected.

All of this taken into consideration, here’s what the new C++ified version of the above code looks like:

#include <Python.h>

namespace py

{

class MyClass : public PyObject

{

// put data members here as you normally would

int someData;

/**

* @param self reference to `this`

* @param args tuple containing all the arguments passed

* @param kwds optional tuple of all the strings used in this invocation

*

* @returns reference-counted pointer to some python object

*/

PyObject* PyMyClass_DoSomething(PyObject* args, PyObject* kwds)

{

// Manually handle all possible overloads by parsing `args` and `kwds`.

// We can access `someData` directly.

// No need to cast `self` to a `PyMyClass`.

// Always return a `PyObject` here, never NULL.

}

// array of all methods this class has

static inline PyMethodDef methods[]

{

{

// the syntactical name for this method in Python

"DoSomething",

Util::UnionCast<PyCFunction>(&py::MyClass::DoSomething),

// flag whether this method takes keywords, no, some, or variadic args, etc.

METH_NOARGS,

"documentation about what this function does"

},

// sentinel declaring the end of this array

{ nullptr }

}

// array of all instance variables

static inline PyMemberDef members[]

{

{

// the syntactical name for this variable in Python

"someData",

// flag declaring its type

T_INT,

offsetof(PyMyClass, someData), 0,

"documentation about the purpose of this variable"

},

// sentinel declaring the end of this array

{ nullptr }

}

// All the type information for this class.

// Think like type_info in C++.

static inline PyTypeObject type

{

// again, saying that we inherit from Object

.ob_base = { PyObject_HEAD_INIT(nullptr) 0 },

// the syntactical name for this class in Python

.tp_name = "MyClass",

.tp_members = PyMyClass_members,

.tp_methods = PyMyClass_methods

}

};

}

The changes here are small and purely semantic, but they make me happy.

Another tricky aspect of the Python C API is reference counting. Python allocates all variables on the heap with reference counters. Yes, even if you declare a simple int, it will always exists on the heap, not the stack, and there’s also a reference counter to go along with it.

In the Python C API, you’re expected to manage the reference counts yourself with Py_INCREF and Py_DECREF macros. It’s important you do so precisely and correctly or else you could cause a dangling reference to never be deallocated or a reference to be destructed prematurely.

This is exactly as tedious and troublesome as it sounds. But why bother? This concept is already solved in C++ through the use of smart pointers. So what I’ve done is create my own py::shared_ptr class which simply stores a PyObject* and manages Python’s reference counts in its special members. Now we have RAII behavior for Python’s types. Nice.

Polymorphism Between Python and C++

The end-goal of what I wanted in Python was to be able to define my own derived-class of Entity and override their Update methods to give them custom behavior. There would also have to be other miscellaneous utilities bound to python such as the game clock so that in Update we can retrieve the delta since the last frame and properly update positions. However, those were ancillary tasks compared to the primary goal of inheritance.

In Python, a demo of that looks like this:

from MyGameEngine import Entity, Time

# inherit from the C++ Entity base class

class MyEntity(Entity.Entity):

pythonOnlyDataMember = 'hello'

# override protected Update to define custom behavior

def _Update(self):

# get a reference to a specific child by name through a public method

child = self.Child('my child name')

# get the delta seconds through a static method

deltaTime = Time.Delta()

child.DoSomething(deltaTime, self.pythonOnlyDataMember)

# invoke the base class Update should you choose

super()._Update()

The most complex part of this is the polymorphic behaviors. So let’s identify what they are specifically:

- We can inherit from a C++ base class.

- We can inherit from a Python class that inherits from the C++ base class.

- We can override methods.

- We should expect polymorphic behavior here on the C++ end as well. That is, if we invoke

Updateon a child that happens to be a Python derived type, we invoke thatUpdatewhich is defined in Python.

- We should expect polymorphic behavior here on the C++ end as well. That is, if we invoke

- We can access the

superclass and invoke its methods. - We can retrieve a child

Entitywhich is perhaps a type defined in C++ or Python, we don’t know.

To address this, I’ve developed two types of Entities:

namespace py

{

// All Python Entities indirectly inherit from this.

class Entity : public ::Entity

{

// reference to a py::EntityBinding

py::shared_ptr pyObject;

protected:

// only invoked through C++ via the parent's `Update()`.

// invokes a Python `_Update()`

virtual void Update() override

{

PyObject* method = PyObject_GetAttrString(&*pyObject, "_Update");

PyObject_CallObject(method, nullptr);

}

};

// Wrapper to all Entities in Python.

// All Python Entities will directly inherit from this.

class EntityBinding : public PyObject

{

// Reference to any type of Entity, not necessarily a py::Entity.

// However this will always be a py::Entity for Python-derived Entities.

std::shared_ptr<::Entity> e;

// only invoked through Python via `super()._Update()`

// invokes a C++ `Update()`

PyObject* Update()

{

if (e->Is<py::Entity>())

{

e->Library::Entity::Update();

}

else

{

e->Update();

}

Py_RETURN_NONE;

}

/**

* @param arg a Python string which must be parsed into a std::string

* @returns an `EntityBinding*` referencing an `::Entity` or `py::Entity`

*/

PyObject* Child(PyObject* arg);

static inline PyMethodDef methods[]

{

{

"Child",

Util::UnionCast<PyCFunction>(&EntityBinding::Child),

METH_O,

"get child by name"

},

{

"_Update",

Util::UnionCast<PyCFunction>(&EntityBinding::Update),

METH_NOARGS,

"initialization ran after construction before the first Update"

},

{ nullptr }

};

static inlinePyTypeObject EntityBinding::type

{

.ob_base = { PyObject_HEAD_INIT(nullptr) 0 },

.tp_name = "Entity",

.tp_members = members,

};

};

}

This is a careful ballet to navigate, so let’s trace through it:

Invoking Python from C++

- We start in a regular C++

::Entity::Update(). - We invoke a child’s

Update(). - That child happens to be a

py::Entity. - The vtable brings us to

py::Entity::Update(). - We hold a reference to a

py::EntityBinding. - Invoke that

py::EntityBinding’s Python-derived_Update() - This is handled through Python’s inheritance system, not C++ vtables.

Invoking C++ from Python in _Update

- We’re in a Python

_Update(). super()is either another Python derivation ofpy::EntityBinding, or apy::EntityBinding.super()._Update()for a Python derivation ofpy::EntityBindingis handled entirely Pythonically.super()._Update()for apy::EntityBindingwill invoke::Entity::Update()which simply invokesUpdate()on all the children (bringing us to step 1 of Invoking Python from C++)

Invoking C++ from Python via Child Reference

- We’re in Python and call

Child()on some Entity. - That child will be a

py::EntityBinding. - Let’s say we invoke

_Update()on that child. - That

py::EntityBindingcould be referencing either a(n):::Entity- goto Invoking Python from C++ step 1.

py::Entity- goto Invoking Python from C++ step 5.

- Python derivation of

py::EntityBinding- goto Invoking Python from C++ step 5.

Hopefully that control flow was easy enough to follow. I should probably come up with a flowchart to visually represent it.

Demo

With the explanation of how I’m binding my C++ engine to Python, let’s take a look at what this can be used for.

Everything you see above is an Entity. Every character is an Entity. The characters exist in clusters that make up another Entity. All these clusters together make up the entire scene, which is yet another Entity. When the parent Entity’s Transform is updated, all the children Entities get their Transforms updated as well.

All of the logic and graphics for this demo are handled in Python. Part of the beauty of these Python bindings is that, even though my engine doesn’t yet support a rendering framework such as DirectX or OpenGL, I can still import a third party library with Python. In this case I’m using asciimatics which is a high-level wrapper to the Curses library. I’ve worked with Curses directly before and this wrapper is refreshingly simple by comparison.

Furthermore, making small changes to the game no longer requires recompiling. For instance, I can edit one line in Python to change the color of the text and simply re-launch the application to now have blue text instead of green.

All modern game engines I can think of are implemented on the back end in highly efficient C++. However, they all also provide some sort of high-level alternative to C++ that both makes their engine more approachable to newcomers and easier to edit on-the-fly. It was a primary goal of this project to explore what goes into creating bindings like these and I’m very happy with the result.

You can find all the source code in this article on my repo.